I have missed two blogs since my last due to familial

obligations and found myself today casting about for a theme to get me back on

track. Since I have an interest in the

origin of drinks, and their names, I thought I would borrow from a previous

effort and use the title “What’s In A Name” with the related drink(s) appended. If this works, I may do more in the future.

In the early 1900's, preceded by the operettas of the 1880's,

the American public became enamored with musical comedy. The play Floradora

receives much of the credit for this craze.

A popular play in England in 1899, Florodora

opened in the Casino Theater of New York in 1900.

In the early 1900's, preceded by the operettas of the 1880's,

the American public became enamored with musical comedy. The play Floradora

receives much of the credit for this craze.

A popular play in England in 1899, Florodora

opened in the Casino Theater of New York in 1900.

The play involves the imaginary island of Florodora

on which a perfume of the same name is made.

Said island was stolen from its rightful owner whose daughter still works

in a factory on the island. The rest of

the plot is convoluted to the extreme but the cast, chorus line, and music seem

to have compensated successfully. A

feature of the theater was a manikin in the lobby spraying “La Flor de

Florodora” on the theatergoers.

After a slow initial start, publicists started promoting the

play in a manner seen repeated by the movie studios in their heyday. TV news coverage of the Kardashians pales to that

given the Florodora troupe. Newspapers featured daily stories about the

cast members, their personal lives, how well they regarded one another and

worked together, their romances and marriage prospects, and of the huge sums of

money that the chorus girls were making by speculating on Wall Street. To the latter, one has to wonder if their

fiduciary success was due more to the stage door sugar daddies than Wall

Street, but maybe I have seen too many old movies. Ultimately, Florodora exceeded 500 performances.

Florodora was the

first musical comedy to use the device

of “stunning” fashionable evening gowns, worn by attractive women, to create a memorable

high point in a performance, a trend continued in the Follies of the 1920’s and

30’s. Women would go to see the latest

fashions, men to see attractively dressed women.

At the time, the music was considered “bewitching,” and

people were often heard humming or whistling the tunes. Leslie Stuart, the composer, said his formula

for writing the music of Florodora

was to:

“…take one memory of Christy

Minstrels, let it simmer in the brain for twenty years. Add slowly for the music an organist’s

practice in arranging Gregorian chants for the Roman Catholic Church. Mix well and serve with a half dozen pretty

girls and an equal number of well-dressed men.”

The original “Florodora sextette” or the “big six,” none

over 5’4”, was so popular with the American public that chorus girls for years

afterwards, claimed to have been part of the original sextette. Francis Belmont, an original “sextetter,” in

true movie showgirl fashion, managed to marry an English duke.

The original “Florodora sextette” or the “big six,” none

over 5’4”, was so popular with the American public that chorus girls for years

afterwards, claimed to have been part of the original sextette. Francis Belmont, an original “sextetter,” in

true movie showgirl fashion, managed to marry an English duke.

Florodora, its

music, and its stars were immensely popular in the early 1900's. Like movie related marketing today, the

musical comedy became linked to a variety of products. A soft drink in Cuba, race horses and

pedigreed dogs, assorted food products, china, dolls, cigars (“three for 10

cents”) and a hybrid long staple cotton named Florodora were but a few. Having a fondness for ice cream, one of my

favorites is the “Florodora Sundae” – 1 banana, strawberry ice cream,

strawberry fruit, nuts, and whipped cream.

In 1920, there was a revival of Florodora, with more chorus girls, and more lavish costumes and

staging. It was so popular that Fannie

Brice was inspired to do a parody in the Follies.

Riding its second

wave of popularity, it once again gave advertisers a useful marketing

hook. Florodora actresses modeled veils in Cosmopolitan magazine. A massage vibrator was advertised to help

women achieve “Florodora” beauty and sponsored a Florodora beauty contest. Use of “Florodora” in marketing persisted into

the 1930’s, as both a product name, and as a derogatory expression for

something passé from a previous era. There was also a movie entitled “The Florodora Girl.”

Riding its second

wave of popularity, it once again gave advertisers a useful marketing

hook. Florodora actresses modeled veils in Cosmopolitan magazine. A massage vibrator was advertised to help

women achieve “Florodora” beauty and sponsored a Florodora beauty contest. Use of “Florodora” in marketing persisted into

the 1930’s, as both a product name, and as a derogatory expression for

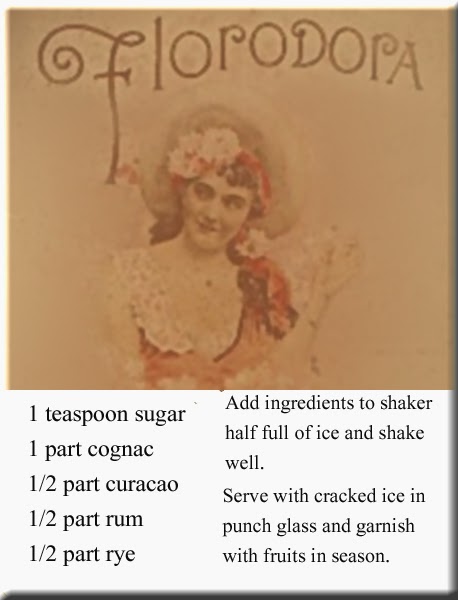

something passé from a previous era. There was also a movie entitled “The Florodora Girl.”In my books, there are at least three "Florodora" related recipes. The first two, the Florodora cocktail and the Florodora Fizz, from a 1913 text, are the earliest recipes I have found. The Florodora Fizz definitely predates the book.

A 1902 advertising magazine, The Advisor, states “The Florodora Fizz

has replaced the Ping Pong Punch as the fashionable drink of the season.”

A 1902 advertising magazine, The Advisor, states “The Florodora Fizz

has replaced the Ping Pong Punch as the fashionable drink of the season.” The Florodora Cooler, easiest for the home bar, is from a publication of the 1930’s. It is probably a Prohibition era drink being gin based, its other ingredients doing well to make the “bathtub” gins of the Roaring Twenties more palatable.